The battle for country parks is not yet won

Afforestation was an urgent task after the war. The Colony was almost entirely deforested. As vegetation became denser the need to arrest fires and litter grew. So also did the voices for nature conservation, public education and recreation in the forests.

The call to establish a ‘national parks’ scheme was answered by colonial governor Murray MacLehose in 1974, with one newspaper reporting the installation of ‘150 tables for picnickers, 135 benches, 110 barbecue pits and 600 litter bins.’ The Country Parks Ordinance was enacted in 1976 and the Country Parks Regulations in 1977. MacLehose was in a hurry: ‘In four years’ time, there will be about 20 parks covering all the open countryside.’

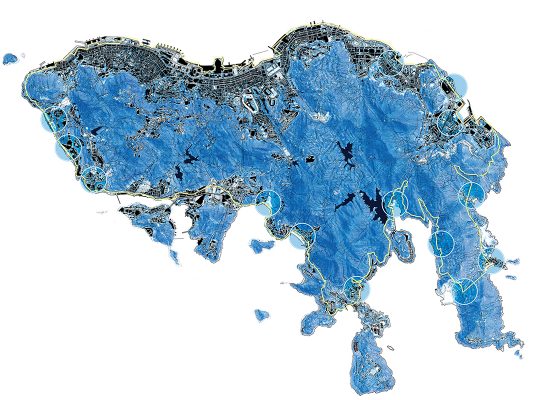

To expedite the designation, some 77 enclaves of private land inside the parks were excluded from the legislation. Most elderly continued subsistence farming in these small and remote villages for some years while their offspring left for factories in Kwun Tong and Tsuen Wan or went overseas.

Access was mostly on foot or by sampan. The few accessible villages close to Sai Kung developed with small houses under the 1972 policy. They became a popular choice for expats including retirees and pilots (before Kai Tak closed). Fast forward, in 1992 the Sha Lo Tung judicial review stopped a golf course development in this enclave famous for butterfly colonies. A six-year long campaign started in 2000 to hold off the creation of a zone for 370 houses at the Tai Long Wan beach enclave.

Sporadic unauthorised development at enclaves culminated in condemnation when the government failed to act on extensive land clearing behind the beach of Tai Long Sai Wan in the summer of 2010. The public demanded protection of the country parks and strengthening of development control. Recognising the enclaves as part of the country parks would put development under the strict Country Park Regulations Ordinance. Land owners, egged on by the Heung Yee Kuk, objected aggressively.

In 2014, the Government excluded their own advisors, the Country and Marine Parks Board, from its decision not to incorporate the village enclaves Hoi Ha, Pak Lap, So Lo Pun, To Kwa Peng, Pak Tam Au and Tin Fu Tsai into Country Parks.

Government did not go further than zoning the enclaves under the Town Planning Ordinance. This offers minimal protection. It does not provide for management or adequate enforcement powers.

On 12 October this year, the Court of Final Appeal ruled otherwise – the Save Our Country Parks Alliance won. The Government is ordered to go back to the Country and Marine Parks Board. Question is now – will they stop the rot and take control over the enclaves? The battle to protect our country parks has yet to be won.

(Based on ‘The battle for country parks is not yet won’ by Paul Zimmerman published in Southside Magazine, 1 November 2020)

郊野公園的抗爭仍長路漫漫

戰後初時,殖民地的植被頓成廢墟,植樹成為一時之急。當森林郊區回復原貌,樹木長回茂盛,撲滅山火的需要以及山野垃圾的數量卻與日俱增,郊區保育、康樂活動及公民教育的聲音亦隨之出現。

1974 年,時任港督麥理浩回應訴求,設立類似「國家公園」的規劃大綱,同期亦有報章報導在郊野公園為行山客安裝 150 張枱、135 長櫈、110 個燒烤爐及 600 個垃圾桶的消息。郊野公園條例及郊野公園規例分別在 1976 年及 1977 年通過立法,而麥對此顯然感到不足,並指出在四年內將會有約20個郊野公園遍布郊區。

為加快立法進度,約 77 個位於郊野公園範圍內,屬私人擁有的「不包括土地」獲得豁免。這些土地擁有者中多為長者,他們把這些土地發展成村落並繼續耕作,其子嗣則選擇到城市的工廠尋找工作機會,或到海外發展。這些村落大多只能步行前往,或以舢舨進入。其中小數如西貢等則因 1972 年的政策發展成丁屋群,在啟德停用前,它們是外籍退休人士及機師的熱門居住地方。

1992 年的沙螺洞司法覆核案阻止在這個蝴蝶棲息地興建高爾夫球場,在 2000 年開展的長達六年的抗爭亦成功否決在大浪灣沙灘周邊的「不包括土地」興建 370 間房屋的計劃。然而,2010 年夏天,政府對大浪西灣沙灘後方的土地清理行為視而不見,零星的違例發展達至高峰。社會大眾要求保護郊野公園,並進一步管制發展開發行為,其一方向就是藉把「不包括土地」納入郊野公園範圍,實施嚴格的發展要求限制。作為地主之一,視鄉郊土地為金蛋的鄉議局,想當然作出強烈反對。

2014 年,政府於未有依法諮詢郊野公園委員會的情況下選擇不把海下、白腊、鎖羅盆、土瓜坪、北潭凹及田夫仔等鄉郊的「不包括土地」納入郊野公園範圍。這顯然未能充分保護「不包括土地」,亦未能為管理及執法提供足夠權力。

今年 10 月 12 日,終審法院判決保衛郊野公園大聯盟勝訴,政府需回到郊野公園及海岸公園委員會重新審視決定。問題是,政府會否下定決心奪回「不包括土地」的掌控權?保護郊野公園的抗爭尚未成功,同志們仍須努力。